Since Edward Snowden stepped into the limelight from a hotel room in Hong Kong three years ago, use of the Tor anonymity network has grown massively. Journalists and activists have embraced the anonymity the network provides as a way to evade the mass surveillance under which we all now live, while citizens in countries with restrictive Internet censorship, like Turkey or Saudi Arabia, have turned to Tor in order to circumvent national firewalls. Law enforcement has been less enthusiastic, worrying that online anonymity also enables criminal activity.

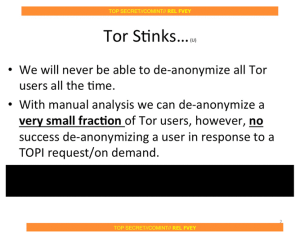

Tor's growth in users has not gone unnoticed, and today the network first dubbed "The Onion Router" is under constant strain from those wishing to identify anonymous Web users. The NSA and GCHQ have been studying Tor for a decade, looking for ways to penetrate online anonymity, at least according to these Snowden docs. In 2014, the US government paid Carnegie Mellon University to run a series of poisoned Tor relays to de-anonymise Tor users. A 2015 research paper outlined an attack effective, under certain circumstances, at decloaking Tor hidden services (now rebranded as "onion services"). Most recently, 110 poisoned Tor hidden service directories were discovered probing .onion sites for vulnerabilities, most likely in an attempt to de-anonymise both the servers and their visitors.

Cracks are beginning to show; a 2013 analysis by researchers at the US Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), who helped develop Tor in the first place, concluded that "80 percent of all types of users may be de-anonymised by a relatively moderate Tor-relay adversary within six months."